Haiku, a century-old traditional form of poetry, originated in Japan and later took the world by storm.

It now holds a position of immense relevance in literature. Its roots can be traced back to the 17th century.

It emerged as a distinct style from the ancient collaborative verse form called renga.

This was characterized by the concise structure of 17 syllables divided into three phrases of 5, 7, and 5 syllables.

Its impact was so huge that its influence went beyond literature, impacted visual arts philosophy, and extended to modern digital communication.

But what is haiku that revolutionized the world of poetry, what is its structure, and more?

In this article, we shall try to figure out these questions in detail and check the detailed ideas around haiku.

What is Haiku?

Haiku is a traditional and established form of Japanese poetry with massive roots in the West.

The main reason behind its gaining prominence was its brevity, which caught students’ attention.

Teachers also find it an extremely interesting addition to the study of poetry.

The best part about haiku is that it has little background information and ideas around the guided practice.

Studying haiku will give a glimpse into the Japanese culture.

If you’re interested in exploring this poetic form further, check out our collection of haiku examples 5-7-5 about life, which beautifully encapsulate everyday experiences and emotions.

Haiku and its Historical Background

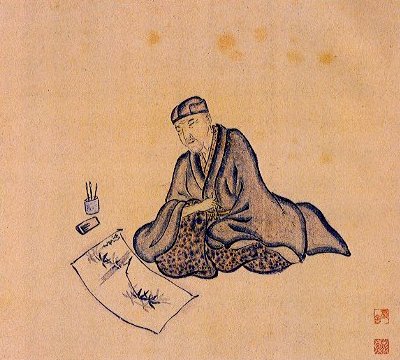

In the 150-plus years of haiku history, only a few poets in Japan gained prominence and are widely respected for their poetry.

Among a few of them are Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki. And out of all four, Basho is the most famous.

He is widely credited for making haiku a recognized form of poetry. It was Basho only because of whom haiku’s refined form started to be used this much.

Before this, the 17 syllables were much more prominent but not with the magnitude and simplicity that Basho transformed them into.

In the year 1644, Basho was born in Ueno. His father was a lower-ranking samurai who worked for the Todo family.

At nine years old, Basho started studying with Yoshitada, the heir to the Todo family.

Two of them became close friends and trained under renowned author Teitoku in the craft of linked verse. Basho was devastated by Yoshitada’s death at the age of 25.

After his appeal to be freed from the Todo family’s service was turned down, Basho flew to Kyoto.

He went on to study Chinese and Japanese classics in a temple there for several years.

When Basho returned to Ueno in 1671, he gave an edited and critically analyzed anthology of writings by numerous authors, including himself, to the shrine there.

After the anthology’s positive reception, Basho’s reputation grew. He quickly departed for Edo, or Tokyo today, the seat of the Tokugawa dynasty.

There, he held a variety of professions while establishing himself as a prominent member of the poetry community.

He received an invitation to study under the renowned modern poet Soen.

Basho learned the value of using ordinary images in a modest and unassuming way from Soen, which became a defining characteristic of his poetry.

Structure of Haiku

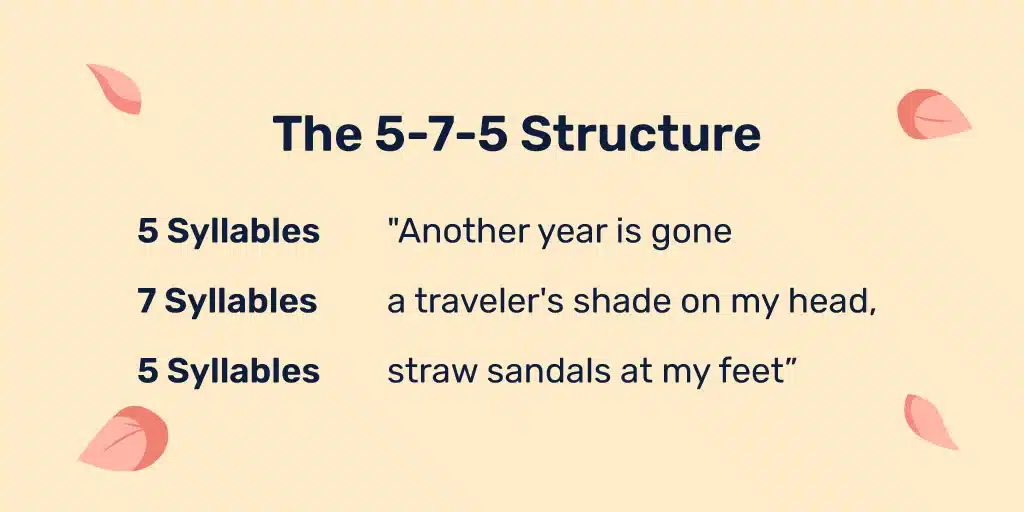

A haiku is a traditional three-line Japanese poetry with straightforward and powerful words and phrases.

The 5-7-5 moras pattern governs the structure of this language. Moras are similar to syllables in that they are rhythmic sound units.

It might be difficult to balance word and phrase meaning and syllable count when translating Japanese haiku into English or other languages.

Japanese haiku have seventeen sounds, or on, which some English translators contend is more like twelve syllables than seventeen.

There may be differences in translation over whether 17 English syllables accurately depict haiku since they are not the same as syllables in English and are, therefore, calculated differently.

Furthermore, haiku in Japanese are written in a single line instead of the two-line style found in most English translations.

Japanese haiku frequently use kireji, or ‘cutting words,’ which produce a pause or break in the poem’s rhythm instead of a line break.

Generally, most haiku poems have the same structure:

- first line: 5 syllables

- second line: 7 syllables

- third line: 5 syllables

Because of its 5-7-5 pattern and structure, a haiku poem typically has three lines and 17 syllables.

Writing Haiku

Writing haiku may appear easy because haiku are short poems or follow a certain syllable count and pattern.

However, this art form requires precise word choice and sequence to effectively produce images to extract an emotional response from the reader, which permits a deeper interpretation and meaning.

Two broader matters require your essential while working on Haiku these are:

1. Subject Matter

Focusing on unique pictures and minute details is one of the extremely crucial aspects when choosing a theme for a haiku poem.

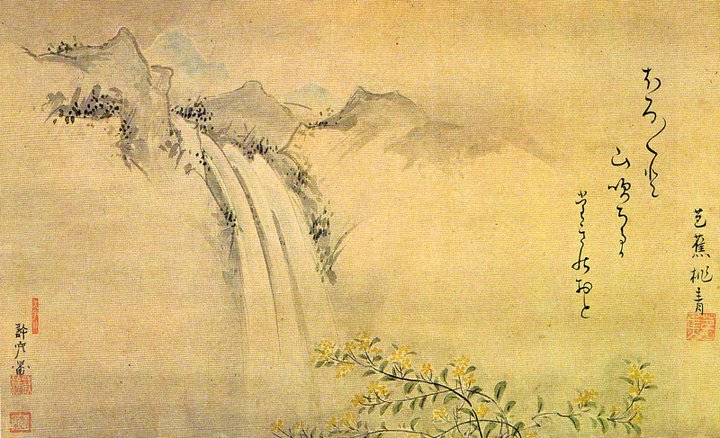

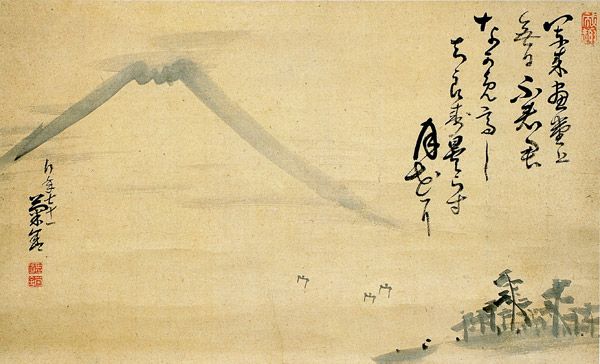

This type of Japanese art frequently features themes of nature. Regarding seasonal variations and how our senses perceive the environment, nature presents captivating and exquisite subjects.

Haiku poetry does a good job of reflecting and portraying life’s straightforward, everyday parts.

2. Language and Wording

When writing haiku, poets should use brief sentences that give rise to powerful feelings and imaginations among the readers.

The Japanese custom of kigo will be extremely helpful in such a situation.

This enables the poet to use a limited number of words to establish the mood and tone of the poem by selecting pictures that represent a certain season.

A poet may use “tender snowflakes” to imply winter and a chilly or serene scene.

Going through this, the reader may feel peace and stillness.

To write a powerful haiku, poets should carefully examine their choice of language, phrase, and punctuation or a ‘cutting word’ (kireji) to establish meter and rhythm.

Conclusion

The Haiku’s legacy in literature is a deep testament to its simplicity, which is widely recognized worldwide.

This minimal form of poetry, whose history dates back to Japan, goes beyond cultural and language boundaries and is connected with people worldwide.

Its structure, a mere 17 syllables, poses a great challenge to poets who express a wide array of emotions and observations within a stipulated linguistic framework.

This boosts creativity and a deep sense of conciseness. Haiku holds the sheer potential to capture the ephemeral nature of life, focusing on the world’s beauty.

The best part about Haiku is it enriches the literary landscape around the globe and gives a lens through which one can view and appreciate the various subtleties of our day-to-day lives.

Share your experience on this journey around Haiku and how you look up to this traditional literary form in the comments below.